By Robert Morgan

In 1969, Peter Fonda and Dennis Hopper, two young actors who had begun their careers in slick studio fare but eventually found themselves detouring into exploitation movies as the old Hollywood studio system collapsed, were on top of the world.

Having pooled their considerable, rarely tapped talents to make a low-budget independent film free of any executive involvement that would stifle their better creative instincts, Fonda and Hopper returned to the backlot haunting grounds of their youth with the beautifully nihilistic drama Easy Rider. The final film, which Hopper directed from a screenplay he co-wrote with Fonda and Terry Southern and featured both actors in the leading roles, was picked up for distribution by Columbia Pictures and went on to become a darling of the critics and a surprising international box office smash.

Easy Rider has often rightly been credited with ushering in the “New Hollywood” of the 1970’s. Audiences were no longer showing up for the latest Julie Andrews musical or John Wayne western in the numbers they once did. The 60’s had been a time of major social and political upheaval throughout the world. Desperate to cash in on the younger moviegoing demographic they had long dismissed that had proven crucial to the success of Fonda and Hopper’s film, the major studios reluctantly proceeded to invite filmmakers with daring and innovative visions that could be realized without massive budgets into their warming embrace.

Universal Pictures was one of the first to seize on this golden opportunity, quickly locking up the next films from the Easy Rider team. It was here that Fonda and Hopper would part ways, with Hopper heading south of Hollywood, and sanity it would seem, to spend the next few years directing the film whose title – The Last Movie – would nearly prove prophetic in more ways than one, while Fonda journeyed to New Mexico to make his directorial debut on the existential western The Hired Hand.

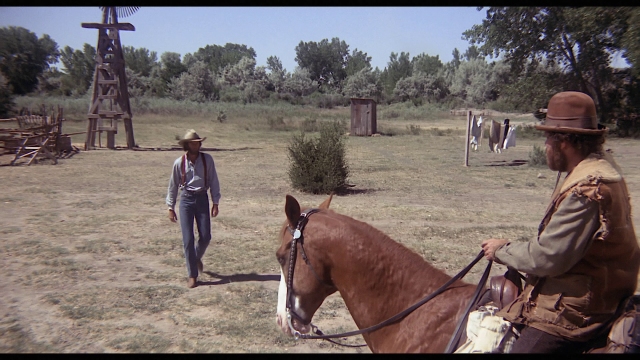

Neither film would live up to the expectations of the Universal suits or the audiences that had shown up in droves for Easy Rider. They attempted to sell The Hired Hand as another action-packed adventure in the Old West, prominently playing up Fonda’s name in the ad campaign, but their marketing efforts were a gross misrepresentation of the elegiac and haunting character study Fonda had made.

Both it and The Last Movie would be subsequently buried in limited theatrical runs and relegated to the bottom halves of double bills before fading into obscurity for decades to come. At least The Hired Hand was granted a minor reprieve when NBC aired an expanded cut in 1973 that restored several scenes deleted by Fonda and editor Frank Mazzola for the theatrical release version.

While Hopper did not possess a single clue as to how The Last Movie would look in its finished form since he began production without a completed script and editing took many months to finish (this process is chronicled in eyebrow-raising detail in Lawrence Schiller and L.M. Kit Carson’s fantastic documentary The American Dreamer), Peter Fonda began shooting The Hired Hand armed with a terrific screenplay by the celebrated Scottish writer Alan Sharp.

On the strength of his script for Fonda’s film, Sharp would go on to write some of the decade’s most underrated releases, including Robert Aldrich’s western Ulzana’s Raid and the bleak Arthur Penn mystery Night Moves. He also scripted the screen adaptation of Robert Ludlum’s suspense novel The Osterman Weekend, which Sam Peckinpah directed as his final film.

The 1970’s was a decade of unconventional westerns. While John Wayne continued to chug ahead with his brand of conservative meat-and-potato oaters, the screens were inundated with far more polarizing and subversive tales of the Old West such as Robert Altman’s McCabe and Mrs. Miller, Peckinpah’s Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, and Philip Kaufman’s The Great Northfield Minnesota Raid. Although some of these features offered grounded takes on historical figures who had been elevated, perhaps unfairly in certain cases, to mythological status, films like McCabe and The Hired Hand told stories with original characters, and they did so in a fashion western fans were unprepared for at that time.

They may have broken new ground in the genre’s portrayal of life on the frontier in the 19th century, but most of them fared poorly at the box office. It wasn’t until a television actor by the name of Clint Eastwood returned to the U.S. after finding film stardom as the cynical outlaw antihero of Sergio Leone’s “Dollars Trilogy” in the late 60’s that westerns returned to their more conventional roots while continuing to offer moviegoers the updated vulgarity, sexuality, and bloodshed they desperately craved.

Seven years prior to the beginning of the story, Harry Collings (Fonda) abandoned his wife Hannah (Verna Bloom) and daughter Janey (Megan Denver) to live the life of a wandering cowpoke with his best friend Archie Harris (Warren Oates). Shortly after Archie expresses a desire to ride out to California, Harry decides instead to return to the farm he once called home and the family he turned away from. Reluctantly, Archie rides along with him.

When they reach the farm, Harry discovers Hannah is unsurprisingly none too pleased to see him after his prolonged absence. Harry pleads with her to let him stay there and work the farm as a hired hand, hoping that the time they spend together will eventually result in a reconciliation. As good help is often hard to come by, Hannah agrees.

The closest the film has to a conventional western villain is McVey, the corrupt and depraved ruler of a small town Harry and Archie spend some time in when the former makes his decision to go home. When McVey is proved to be responsible for the murder of their young friend and traveling companion Dan Griffen (Robert Pratt), Harry and Archie attack him at his home, wounding him in the foot in the process. McVey is out of the film until the third act when he puts Harry in a difficult position where he will once again have to leave Hannah and Janey behind to seek some old school vengeance.

The role of McVey was played with smirking, gentlemanly evil by Severn Darden, the character actor and alum of the fabled Second City improvisational comedy collective whom is most familiar to fans of the Planet of the Apes franchise as the evil Kolp in Conquest of the Planet of the Apes and Battle for the Planet of the Apes. He also made countless guest appearances in film and television throughout his career, including The President’s Analyst, They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?, Vanishing Point, Mother, Jugs, & Speed, Saturday the 14th, and Real Genius.

Although The Hired Hand does conclude with the sort of violent gun battle that typically ends westerns, the central conflict is an emotional one. Hannah, despite her willingness to give Harry a chance to rejoin the family he voluntarily gave up, is up front with her husband about the fact that she quickly moved on after he left. During a trip into town with Archie to get some supplies, Harry is confronted by a man who claims to have once been Hannah’s hired hand, and he implies that she frequently took the men in her employ into her bed.

This understandably unnerves Harry because he senses its truth, but when he later brings up the man’s implication with Hannah, she makes it clear to him that it is true, and Harry has no right trying to make her feel bad about pursuing sexual relationships with other men when he was the one who abandoned her in the first place. No average frontier farm woman waiting patiently one lonely evening after another for her knight in dusty leather armor to return home, Hannah refuses to be slut-shamed by anyone, especially an errant husband who chose the life of an aimless bum over his responsibilities to the wife and daughter he supposedly still loves.

The stronger relationship in the film is the one that develops between Hannah and Archie. In their scenes together, the characters display a mutual attraction that can only be found between the lines, as neither person ever comes out and communicates directly how they really feel about the other. Regardless, we get the sense that Hannah sees in Archie the decent, honorable man she wishes Harry had been all along.

When Archie leaves the farm to strike out for the coast by his lonesome and runs afoul of McVey and his goons, Harry chooses to leave his family once more to risk rescuing his dear friend, a gambit that could very well result in his death. What remains unspoken by the film’s end is the feeling on Archie’s part that Harry should have stayed at home and been the husband and father Hannah and Janey deserved. Some causes, and people, simply are not worth giving your life for, a stark repudiation of the typical western finale that underscores the climatic action sequence in The Hired Hand.

There is much that is left unsaid in this film. For instance, we never find out why exactly did Harry leave behind a loving family to wander the open country in the first place. Maybe he felt suffocated by domesticity. Maybe he considered himself a failure to Hannah and Janey and figured they would be better off without him. In the end, the reason for his departure matters little. What matters is that he came home, and Hannah found it in her heart to give him a second chance. Sometimes action defines character better than words, and the characters of The Hired Hand appear to prefer letting the past be past. The future is what is important to them now.

The final moments of the film carry with them an aching sadness for what could have been, but also a modest hope for what could still be. Without spoiling the ending of The Hired Hand, whether it is a happy one depends entirely on the perspective of the viewer.

Fonda’s performance as Harry is excellent and understated, which I think is best suited for a character who never comes across as the most dynamic in the film. Really, it is Warren Oates and Verna Bloom who carry the emotional weight of The Hired Hand beautifully with acting turns that allow them to dig deep into the pain and sorrow from which their characters draw the strength to endure. Bloom is a force to be reckoned to be with as Hannah, a fiercely independently woman of the plains who rejects the judgment of hypocrites. Quietly compelling in the role of Archie, the legendary character actor Oates, much like Bloom, manages to craft an interesting and sympathetic three-dimensional human being from the sparse frontier poetry of Sharp’s screenplay and the circumspect direction by Fonda.

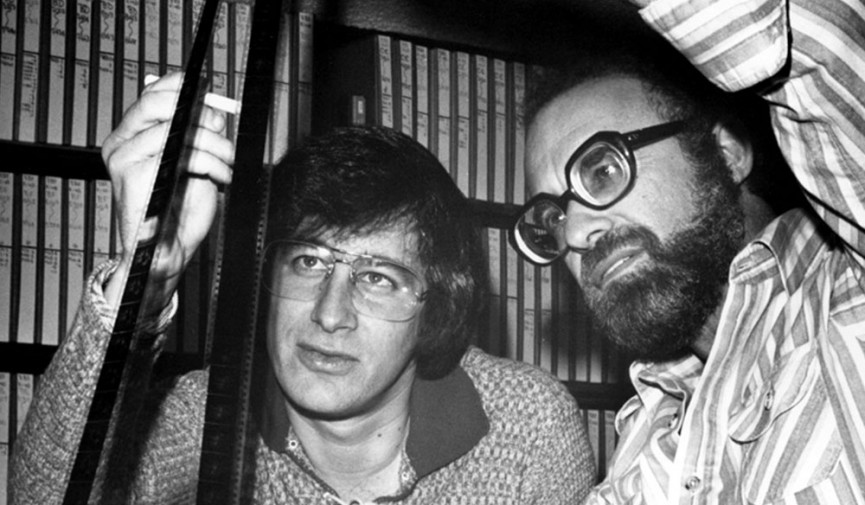

What makes The Hired Hand such a spellbinding film is not limited to the acting and direction. With an estimated budget of $1 million on hand to make his directorial debut, Fonda carefully stocked his behind-the-camera team with true artists willing to work for peanuts in the name of creating truly astounding cinema. Fonda had gotten to know his chosen cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond during the filming of Easy Rider, as Zsigmond had been a close friend of that feature’s cinematographer Laszlo Kovacs. Upon receiving the green light to make The Hired Hand, the young director knew exactly who he wanted to be his cinematographer.

The same year he shot The Hired Hand, Zsigmond had also been employed by Robert Altman to create the gorgeous photography on his own unorthodox western, the aforementioned McCabe and Mrs. Miller. Early in his amazing career, Zsigmond proved far more than capable of producing painterly images through his camera lens. He brings that same gift to Fonda’s film, and his visuals of Harry and Archie making their despairing journeys through unforgiving deserts and across rivers alive with cool, raging waters are among the finest work Zsigmond ever produced. On New Year’s Day 2016, he died at his home in Big Sur, California. He was 85.

Fonda hired Frank Mazzola, a former young actor (his best-known film credit was as the minor character Crunch in Rebel Without a Cause) turned editor, to whip the multiple reels of eye-popping scenery and emotionally-charged drama into a tight 93-minute film that could hopefully make a nice little profit for Universal. Mazzola started his editing career working uncredited on Donald Cammell and Nicolas Roeg’s mind-bending Performance and would go on to edit other Cammell films like Demon Seed and Wild Side. He also worked on the backwoods exploitation classic Poor Pretty Eddie.

Mazzola’s editing gives the sparse action scenes force and immediacy and allows the quieter dramatic moments to play out without needless cuts. He also created several memorable montages out of Zsigmond’s pastoral imagery, initially against Fonda’s orders, but the director was quickly won over by his editor’s creations and the montages stayed in the final film.

The last important of the puzzle that is The Hired Hand’s greatness is the original music score composed by Bruce Langhorne, a famed folk musician and session guitarist who performed on several of Bob Dylan’s earliest classic albums and even inspired the title character in Dylan’s “Mr. Tambourine Man”. A key player in the folk music revival of the 50’s and 60’s, Langhorne also collaborated with famous troubadours of the time such as Richie Havens, Buffy Sainte-Marie, Gordon Lightfoot, Tom Rush, and Peter, Paul & Mary.

Langhorne’s score for The Hired Hand incorporates instruments like banjo, sitar, and fiddle – all of which he played solo while watching a black & white copy of the final edit at his home recording studio. Alternately elegant, peaceful, and discordant, the austere soundtrack often expresses the simmering emotions of the film’s three principal characters better than any dialogue could. Langhorne would later compose the scores for two other Peter Fonda films, Idaho Transfer and Fighting Mad, as well as Bob Rafelson’s Stay Hungry and Jonathan Demme’s Melvin and Howard. He passed away at the age of 78 on April 14, 2017 in Venice, California.

Unavailable on home video for decades and rarely seen on television outside of the extended cut created for NBC’s broadcast, The Hired Hand was finally restored to its intended length with remastered picture and sound in 2001. After playing the film festival circuit to enthusiastic raves, the film received its first legitimate video release in the form of a DVD distributed by the Sundance Channel’s home entertainment division.

Recently, it was released on Blu-ray by the U.K.-based Arrow Video in an edition that is available for a decent price on both sides of the Atlantic. The disc features a commentary with Peter Fonda, a length retrospective documentary produced for the first DVD release with interviews with many of the surviving players (including a few who have since passed on, including Zsigmond and Langhorne), the deleted scenes that were restored for the NBC broadcast cut (among them a subplot featuring Larry Hagman as a local sheriff), and many more features exclusive to the Arrow release. I highly recommend it.

Forty-seven years after it was unceremoniously buried in its theatrical release and nearly lost to the ages, The Hired Hand can finally be regarded as the haunting, unpredictable, and surprisingly tender minor masterpiece of the western genre it has always been.

You can order the Arrow Video Blu-ray release of The Hired Hand HERE and the Bruce Langhorne soundtrack HERE